The stadium lights had barely dimmed when the conversations began.

Some fans were still filing out of the gates, their voices echoing in the long concrete corridors beneath the stands. Others lingered in parking lots, leaning against trucks and folding chairs, replaying the night in fragments. The game itself had been electric—tight, physical, dramatic until the final whistle—but what people kept talking about was not the touchdown that changed momentum, nor the defensive stand that sealed victory. It was the halftime show.

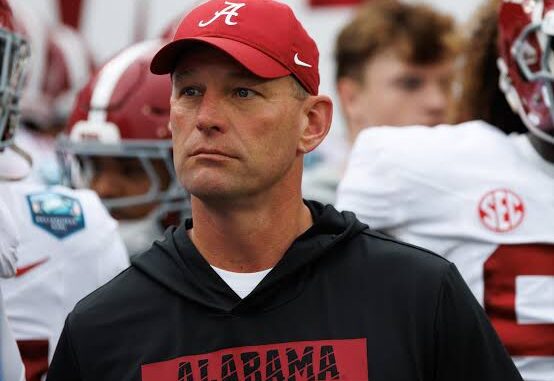

And more specifically, it was what Alabama head coach Kalen DeBoer said afterward.

“Nobody understood what he was saying,” DeBoer remarked when asked about Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance. “And the choreography reflected that.”

The comment traveled faster than the highlights of the game. Within minutes it was clipped, replayed, debated, and dissected. Within hours it had become something larger than a reaction to a halftime performance. It was now a conversation about football itself—what it represents, what it protects, and what belongs on its grandest stage.

To understand why DeBoer’s words carried such weight, one has to understand the emotional architecture of football in America. The sport has never been just a game. It is ritual, theater, discipline, identity, and spectacle layered into one experience. The Super Bowl, especially, has grown into something that resembles a national ceremony—a moment when competition and entertainment merge into a single narrative about excellence, unity, and performance under pressure.

DeBoer, known for his controlled demeanor and deliberate speech, did not appear angry when he made the remark. He appeared precise. Analytical. As though he were reviewing film from a game that had gone wrong.

He described the Super Bowl as a crossroads. A meeting point between elite competition and popular culture. A space where everything—every sound, every movement, every image—should reflect a shared sense of purpose.

According to him, the halftime show had not done that.

In the hours following the game, reporters pressed him for clarification. They expected him to soften his position, perhaps frame his reaction as a matter of personal taste. He did not. Instead, he leaned deeper into his philosophy of what the Super Bowl represented.

“The field is a place of discipline,” he explained. “Everything that happens around it should respect that. The players prepare their entire lives for that moment. The coaches build systems around precision and accountability. When you put something on that stage, it should reflect that same clarity. It should speak to the collective experience—not just demand attention.”

He paused before adding something that would become the most quoted line from the entire exchange.

“Performance without connection is just noise.”

For some, the statement felt like an old-school football mind resisting cultural change. For others, it sounded like a defense of tradition. But inside locker rooms and coaching offices across the country, the reaction was more complex.

Football is built on structure. Plays are rehearsed thousands of times before they ever appear in a game. Movement is synchronized. Communication must be immediate and precise. Even emotion—celebration, aggression, resilience—is expressed within a framework shaped by training.

From that perspective, DeBoer’s criticism was less about language or music and more about alignment. He believed the halftime show should mirror the same intentionality that defines the game itself.

In his view, the performance felt disconnected from that rhythm.

Several of his former players later described what it was like to play under him. They spoke about practices where timing was measured down to fractions of seconds. About meetings where communication had to be exact—no vague instructions, no ambiguous signals. If something lacked clarity, it was reworked until everyone understood it without hesitation.

They said he believed shared understanding was the foundation of any successful system.

So when he said nobody understood what was happening on stage, he wasn’t merely commenting on lyrics or choreography. He was identifying what he perceived as a breakdown in collective experience.

The Super Bowl, he argued, belongs to everyone watching. Not just as spectators, but as participants in a shared moment. When something appears that large portions of the audience cannot interpret or connect with, he believes the unity of the event fractures.

That idea struck a nerve because the Super Bowl halftime show has long been a symbol of cultural evolution. Over the decades it has expanded, shifted, and reinvented itself repeatedly. It has embraced spectacle, experimentation, and global influence.

Yet football itself has remained rooted in tradition even as it adapts strategically. The rules change, the strategies evolve, but the emotional core of the sport—discipline, teamwork, preparation—remains constant.

DeBoer’s critique seemed to emerge from that tension.

Observers noted that he never attacked the performer personally. He never questioned talent or popularity. Instead, he focused entirely on context. He described the Super Bowl as a stage that demands alignment with the values embodied on the field.

He spoke about identity—not in the sense of exclusion, but in the sense of coherence.

“A championship game is about collective effort,” he said during a later interview. “Everything around it should reinforce that idea. The music, the visuals, the storytelling. It should feel like part of the same experience. When it feels separate… when it feels like something dropped in from another world… that’s when it loses meaning.”

Fans responded in dramatically different ways.

Some agreed completely. They described watching the halftime show and feeling detached, as though the spectacle had little connection to the emotional intensity of the game they had just witnessed. They wanted something that amplified the tension, the unity, the sense of shared investment.

Others argued that contrast is precisely what makes halftime memorable. They believed the stage exists to expand the event beyond football, to reflect the diversity of audiences and cultures that now surround the sport.

But even those who disagreed with DeBoer acknowledged something unusual about his comments. He had framed the discussion in philosophical terms rather than cultural ones. He spoke about structure, coherence, and collective meaning—concepts deeply embedded in football itself.

Former players who had experienced championship environments recognized the language immediately. They understood what he meant by alignment. By clarity. By shared understanding.

One retired quarterback described it this way: when a team runs a play perfectly, every movement makes sense in relation to every other movement. The entire formation functions like a single organism. If one part moves without connection to the rest, the play collapses.

He suggested that DeBoer viewed the halftime show as a kind of symbolic extension of the game’s structure. And from his perspective, the symbolic play had broken down.

The debate grew larger with each passing day, not because of the performance itself but because of what it revealed about how people interpret football’s cultural role.

Is the Super Bowl primarily a sporting event that incorporates entertainment? Or is it an entertainment spectacle anchored by a sporting event?

That question has lingered for years, but DeBoer’s comments brought it into sharp focus.

Inside Alabama’s training facility, players reportedly discussed the controversy with curiosity more than tension. Some agreed with their coach’s emphasis on unity. Others viewed halftime as separate from competition entirely. Yet nearly all acknowledged that his reaction was consistent with how he approaches everything connected to football.

For him, the game is not merely played. It is constructed. Every element surrounding it contributes to the environment in which competition unfolds.

Even atmosphere matters.

Even symbolism matters.

Even what happens when the players leave the field for twelve minutes matters.

One assistant coach described DeBoer’s worldview in simple terms: football is a system of meaning, not just motion. It teaches discipline through repetition, trust through coordination, identity through shared effort. Anything placed alongside it on the same stage becomes part of that meaning whether intended or not.

From that perspective, his critique was inevitable.

As the discussion continued across sports media, another layer emerged. Some analysts suggested that DeBoer’s reaction reflected a broader anxiety within football culture—the challenge of maintaining tradition in an era of constant transformation.

The game has become faster, more global, more commercially expansive than ever before. Its audience spans languages, backgrounds, and expectations that differ dramatically from those of earlier generations.

Perhaps what DeBoer expressed was not resistance to change but concern about coherence in a rapidly expanding cultural environment.

If football becomes a meeting place for everything, what ensures it still feels like football?

That question lingered beneath every argument about the halftime show.

Weeks after the Super Bowl, the performance itself had faded from daily conversation. But DeBoer’s remarks remained. They continued to surface in coaching clinics, sports radio discussions, and locker room debates.

Because ultimately, his criticism forced people to articulate what they believe the sport represents.

Is football simply competition?

Is it entertainment?

Is it tradition?

Is it identity?

Or is it all of these at once, balanced in delicate proportion?

On a quiet afternoon at Alabama’s practice field, long after the noise of the controversy had settled, DeBoer was asked one final question about the situation. Did he regret saying what he said?

He shook his head.

“Football teaches us that clarity matters,” he replied. “If something feels out of place, you address it. Not because you want conflict, but because you want alignment. That’s how teams grow. That’s how systems stay strong.”

He looked out across the empty field, where yard lines stretched in perfect parallel across the grass.

“This game is built on people moving together toward something shared,” he continued. “That’s what makes it powerful. That’s what makes it meaningful. When something interrupts that… when something pulls attention without contributing to that unity… it stands out.”

He paused briefly, then added in a quieter tone.

“And when it stands out, people notice.”

The stadium lights may have faded that night, but the conversation they illuminated continued long afterward. Not just about a performance, but about the meaning of football itself—its structure, its identity, and the invisible threads that hold millions of viewers together for a single, shared moment.

Leave a Reply