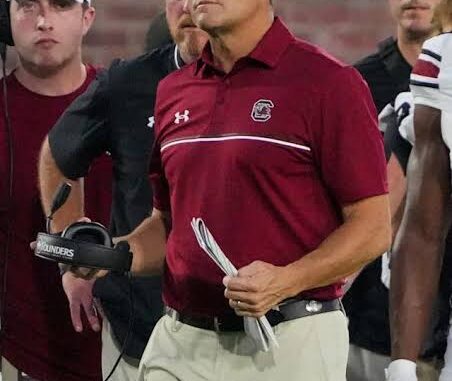

Shane Beamer did not raise his voice. He did not name enemies. He did not accuse specific programs or point fingers at rivals swimming in booster money and transfer leverage. That is precisely why his words detonated so loudly across the landscape of college football. In an era where outrage is often manufactured through theatrics, Beamer chose something far more dangerous: a calm, philosophical challenge to the very moral foundation of the modern NCAA system. What he questioned was not South Carolina’s place in the pecking order, but whether the sport itself still understands what it is pretending to value.

At the heart of Beamer’s remarks was a simple, uncomfortable question: if building a program the “right way” is no longer enough to compete, then what exactly does “right” mean anymore? College football has always sold itself as something more than professional sports with smaller stadiums. It marketed culture, loyalty, development, identity, and continuity. Fans were told they were rooting for something deeper than transactions. Beamer’s warning was that this narrative may now be a lie the sport tells itself to feel better about what it has become.

For decades, South Carolina existed as a program defined by effort rather than entitlement. It was never the easiest destination, never the first call for five-star mercenaries chasing immediate glory. Its identity was built on players who stayed, suffered, developed, and ultimately became something larger than their recruiting rankings suggested. That approach once felt noble, even competitive. Now it feels increasingly like a disadvantage dressed up as virtue.

The Transfer Portal has not merely changed roster management. It has changed incentives, psychology, and the social contract between player, program, and fan. Loyalty used to be an unspoken expectation. It wasn’t absolute, and it wasn’t always fair, but it existed. Players understood that development required patience, and programs understood that investment meant commitment. The portal shattered that balance. It introduced a constant marketplace where dissatisfaction is no longer a phase to work through, but an opportunity to cash in elsewhere.

Beamer’s comments forced the sport to confront a harsh possibility: that patience, development, and culture may no longer be competitive assets, but liabilities. In the new ecosystem, the fastest way to improve is not to coach better or recruit smarter, but to shop aggressively. Programs that once prided themselves on continuity now find themselves punished for it. Meanwhile, those willing to treat rosters like revolving doors are rewarded with instant relevance.

This is where Beamer’s “hand grenade” truly landed. He was not complaining about losing players. He was questioning whether the system itself is now hostile to the values it claims to celebrate. If the best players are incentivized to leave the moment adversity appears, what does that say about the concept of team? If coaching staffs are judged not on development but on portal wins, what does that say about teaching? And if success increasingly correlates with financial muscle rather than institutional identity, what does that say about competitive integrity?

College football has always had inequality. Power programs have always had advantages. But there was once a belief that culture could close gaps, that development could level fields, that a well-run program could punch above its weight. Beamer’s warning suggests that belief may now be obsolete. The gap is no longer just about facilities or recruiting reach. It is about access to a constant stream of ready-made solutions, bought rather than built.

South Carolina sits at the center of this tension. It is not poor, but it is not unlimited. It is not irrelevant, but it is not dominant. It occupies the uncomfortable middle ground where ideals clash with outcomes. If it refuses to fully embrace the portal arms race, it risks being left behind. If it embraces it too aggressively, it risks losing the very identity that made it worth defending in the first place.

That is why Beamer’s question resonates beyond Columbia. Every program that sells culture as its brand now has to answer it. Are we developing players, or auditioning them? Are we building teams, or assembling temporary alliances? Are we teaching resilience, or quietly encouraging exit strategies?

The portal has also altered the fan experience in ways that are rarely acknowledged. Fans once formed emotional bonds with players over years. They watched freshmen struggle, sophomores grow, juniors emerge, and seniors lead. That arc created attachment. Now rosters churn so quickly that emotional investment feels risky. Why buy a jersey when the name on the back might be gone by spring? Why celebrate a breakout season when it may simply serve as a résumé for another program?

Beamer’s words tapped into this growing sense of alienation. College football is becoming harder to recognize, not because of innovation, but because of impermanence. The sport is losing its memory. Traditions feel thinner when faces change constantly. Rivalries lose texture when rosters reset annually. Identity becomes marketing rather than lived experience.

There is also a quieter ethical question beneath Beamer’s critique. The portal is often framed as empowerment, and in many ways it is. Players deserve freedom. They deserve options. But freedom without structure often favors those already positioned to exploit it. The most stable programs benefit the most from instability elsewhere. The richest benefit most from the marketplace. What is sold as liberation can quickly become stratification.

Beamer did not argue for rolling back the clock. He did not deny the injustices of the old system. What he challenged was the assumption that the current trajectory is unquestionably progress. He asked whether replacing one flawed system with another, equally distorted one truly counts as improvement.

South Carolina’s dilemma now feels symbolic. Is it destined to be the final fortress to crumble, eventually abandoning its ideals in order to survive? Or can it become a solitary beacon, proving that culture and development still matter, even in an unforgiving environment? That question may ultimately define Beamer’s tenure more than wins and losses.

History suggests that systems eventually reward efficiency over romance. The cold logic of optimization rarely pauses for sentiment. Yet sports have always thrived on stories, not spreadsheets. College football’s appeal has never been purely about excellence. It has been about belonging, continuity, and shared identity. If those erode completely, the sport risks becoming something technically successful but emotionally hollow.

Beamer’s warning landed because it articulated a fear many have felt but struggled to name. That the sport is drifting toward a future where values are cosmetic, loyalty is transactional, and development is optional. Where slogans about “doing it the right way” are preserved only as branding tools, not guiding principles.

Whether the NCAA listens is almost beside the point. The grenade has already gone off. Coaches are now forced to reconcile what they say with what they do. Fans are forced to reconsider what they are cheering for. Programs like South Carolina are forced to decide whether integrity is still a competitive strategy or merely a comforting myth.

If loyalty has officially ended, college football will survive. Money ensures that. But something irreplaceable may not. Beamer’s challenge was not a demand for sympathy. It was a demand for honesty. And in a sport built on tradition, honesty may be the most disruptive force of all.

Leave a Reply